Chris Roark, croark@cherryroad.com

When MGySgt. (Ret.) Brent Dorrough applied to become the first coordinator of the Ellis County Veterans Treatment Court (ECVTC) he admits there were several things he had to consider.

But once he observed similar programs in nearby counties and saw the difference they have made for veterans who had fallen on hard times, Dorrough knew leading the ECVTC was the best career move he could make.

Dorrough, who was hired as the ECVTC coordinator Jan. 16, has spent the last few weeks finalizing logistics and connecting with resources ahead of the program’s tentative launch date of March 1. It’s an aggressive timeframe, but Dorrough said there’s a lot at stake.

“We’re going to continue to build this,” Dorrough said. “We’ll grow it throughout the year. But the more time we take to bring it up and get it ready to go that’s maybe a veteran that’s not getting helped.”

Ellis County Veterans Treatment Court

The ECVTC has been in the works for over a year. The Ellis County Commissioners Court approved it in late 2022 with the support of District and County Attorney Ann Montgomery. The program is being funded by a $110,000 grant from the Texas Veterans Commission.

Dorrough will work closely with William Wallace, district judge of the 378th Judicial District Court, as well as ADA Jeff Bullock, attorneys Chad Hughes and Danny Freisner, and several area resources – counselors, psychologists, etc.

The purpose of the program is to provide treatment, education, resources and rehabilitation to veterans dealing with mental health issues from their time in the military who are first-time offenders of certain crimes. The program is voluntary, but if the veteran pleads guilty, participates in the program and completes it they can avoid jailtime and have the charge expunged from their record.

“We’re going to give them a U-turn,” Dorrough said. “But on that route back, man, there are so many checkpoints that they really have to be present for. The motivation to get in the program is easy. The discipline to stay in the program, that’s going to be hard.”

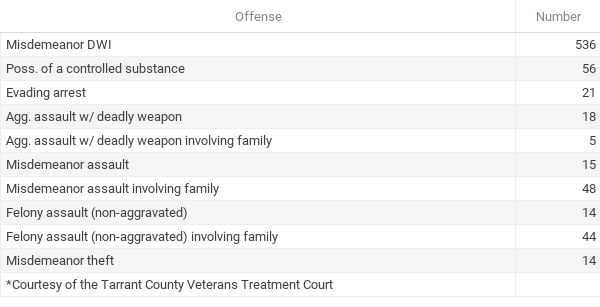

Dorrough said he expects most of the program’s participants to have had DWI offenses, though there may be some with other charges as well, such as controlled substance possession.

The program will not accept offenders charged with what’s known as 3G offenses – crimes where the inmate is required to serve half the sentence before becoming eligible for parole, such as violent or sexually motivated offenses. Other exclusions include three or more DWI convictions, delivery of a controlled substance and others.

Dorrough said ECVTC is an alternative to the current system where first-time offending veterans spend time in jail and a lot of money in the process, often leading to a downward spiral.

“For these guys it’s probably a one-time thing,” Dorrough said. “It’s a snapshot in time. It’s not definitive of who they are. They just didn’t have a good mechanism to cope. And the DWI is simply a symptom of that, and couple of bad choices rolled into one. Now they find themselves in trouble.”

How it works

Dorrough said the four-phase program actually begins when a veteran is arrested. Once the officer learns the offender is a veteran, that will trigger an assessment/verification process as part of phase one.

Phase one also includes orientation and stabilization, which lasts for a minimum of 90 days. Dorrough said he and the ADA will determine if the offender is a good fit for the program.

Once that’s established the participant begins phase two of treatment and education, which lasts a minimum of 120 days.

Phase three includes education and transition, also for a minimum of 120 days.

“They have people come in there and give training on finances, home buying, job placement … the collateral things that you need to make it work,” Wallace said.

The final phase is transition and graduation. The entire process could take more than a year.

Dorrough said in each phase the participant receives the assistance, treatment and rehabilitation (if necessary) they need through a variety of the program’s connected resources, some of which the veteran will have to pay for.

“We’ll have the resources because the program is designed to help fix the root problem, not just the symptoms of it,” Dorrough said.

Each participant will work with a mentor who is a veteran and has experienced the same types of challenges they have.

Throughout the program there are multiple required steps the offender must take, including random urinalysis, blood-alcohol checks, required training, log sheets, etc. Dorrough said he will constantly be in contact with the defendant. And twice a month the defendant will stand before Wallace in the courtroom to update him on their progress. Not staying on task results in a sanction. Another arrest and the veteran is removed from the program.

“It’s very demanding, but it’s done so in a very professional and compassionate way,” Dorrough said. “Because at some point everyone who is in the program raised their hand and swore an oath to our country to go and protect the freedoms and liberties we have here.”

Why it’s needed

According to All Rise, an organization that focuses on the justice system related to substance abuse and mental health, 1 in 5 veterans have symptoms of a mental health disorder or cognitive impairment. Dorrough said a program like this is needed to help them.

In fact, he said the ECVTC will follow the 2009 model – when the state first approved the program – that focuses mostly on combat-related issues.

A typical case could be a veteran who has documented post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a brain injury, trauma, etc. and they are using alcohol to cope but later get arrested for a DWI, Dorrough said.

He said many deployed veterans experience high-stress situations in combat zones, leading to post-traumatic stress (PTSD), traumatic brain injuries (TBI) or other injuries. He said those can derail emotional control and lead to interpersonal conflicts and/or erratic behaviors.

“Decades of research have shown that veterans often have a difficult time readjusting to civilian life and have a higher-than-normal prevalence of mental health and substance abuse issues, which frequently result in illegal, violent and/or risky behaviors,” Dorrough said. “Veterans need to be provided with educational and therapeutic services as alternatives to spiraling deeper into the criminal justice system.”

He said this program will help reduce recidivism.

“Unfortunately, many jails and prisons are unable to offer adequate mental health and substance abuse treatment to the incarcerated,” Dorrough said, adding that it costs approximately $95 per day to house each inmate.

Positive impact

Dorrough said the veterans treatment court in Ellis County will be similar to the one in Tarrant County. And he’s hoping for similar success.

The Tarrant County Veterans Treatment Court begins with an intake process that includes verification, orientation, evaluation and approval into the program.

If approved by the DA’s office the participant starts the three-phased program that includes treatment and medication management. Throughout the program counseling and education services are available, and progress will be tracked through compliance hearings, working with a case manager, etc.

Courtney Young, program manager for the Tarrant County Veterans Treatment Court, said he has seen a lot of lives improved with the program.

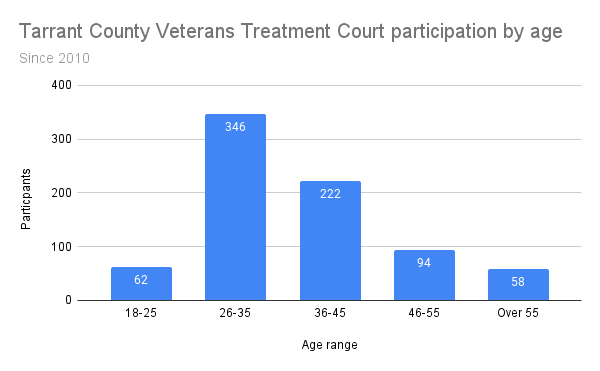

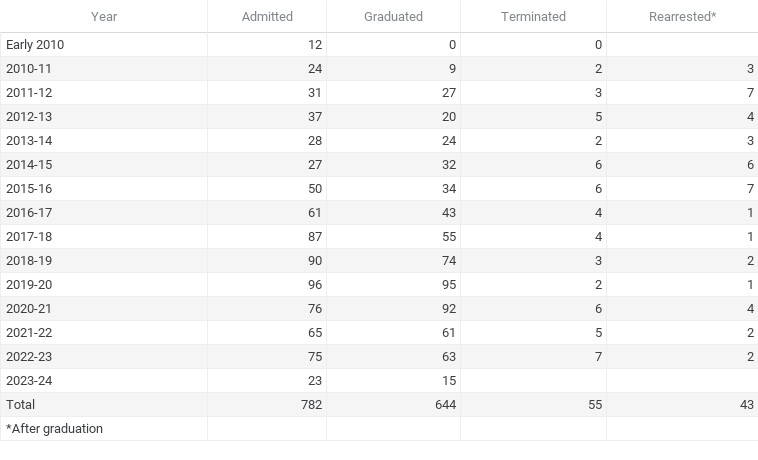

According to Young, there have been 782 individuals admitted into Tarrant County’s program since it began in 2010, and 644 have graduated, a 92-percent success rate. Young said it has yielded a 7 percent recidivism rate, compared to 30-40 percent of the general population.

“At first they’re mad about being here,” Young said. “But soon things start to change. They see other veterans who are dealing with the same issues. Then they realize, ‘Man, I’ve had a problem, and there was nobody there to give me an opportunity to address it.’”

Young said seeing participants come back to the veterans treatment court and mentor others is further proof of its success.

Dorrough and Wallace have visited multiple specialty courts in North Texas, including the veterans court in Tarrant County.

One thing they noticed was the participation. Dorrough said the courtroom was filled with the defendants’ supporters and their resources such as personal counselors, marriage counselors, etc.

“It was packed,” Dorrough said.

Dorrough said the program is voluntary, noting that offenders could just pay their DWI fines, which could cost tens of thousands of dollars, and move on.

But he said if Tarrant County’s program is any indication most offenders will opt in.

Dorrough also noticed the cordial, caring and free-flowing conversations between the veteran and the judge.

“It was very personal,” Dorrough said. “What I saw in court validated my decision. I knew it was the right path for me on day one.”

Wallace said he, too, has observed the Veterans Court in Tarrant County.

“It’s inspiring to see the veterans who are putting their lives back on track,” Wallace said.

Dorrough said he and Wallace will continue to collaborate with judges and coordinators in other programs to develop more ideas.

Valuable experience

The ECVTC will be led by several people with military and/or judicial experience, all who want to help provide a better path for veterans in need.

Dorrough spent 30 years in the U.S. Marine Corps, the last 10 as master gunner sergeant, the highest rank.

He said his experience will help establish a connection to the veterans who participate in the program.

“I’ve been to combat numerous times, I’ve been on deployment numerous times,” Dorrough said. “And I’ve lived the life they’ve lived in the past, so we have that parallel relationship right out the gate.”

Wallace said Dorrough’s experience made him the right person to lead the ECVTC.

“We had a number of very, very good applicants,” Wallace said. “What made Brent such a good choice was his breadth of experience working with Marines of all ages. He has been a human resources person, a person in leadership solutions. He’s worked for very demanding colonels and generals. He’s been able to find the balance necessary to develop a program like this and move it forward.”

Wallace served in the military for eight years – the United States Marine Corps Reserve, the United States Army Corps of Engineers and the Texas Army National Guard.

Wallace has been a district judge for six years. He said in his role as judge, in particular the family docket, he has seen many types of cases that he expects to see in the Veterans Court.

“I have watched families be destroyed when someone with PTSD or a substance abuse problem does not get the right resources to help them,” Wallace said. “And I believe this program will help families and children to preserve them and to make them stronger.”

The two attorneys working for the ECVTC are also veterans.

What’s next

Dorrough said while the scope of the ECVTC will be small initially he hopes it will ultimately be a beacon for other counties.

“My goal is to be a great program,” Dorrough said. “I want ours to be the model that people come to see next year.”

Dorrough also wants to see it be a launching pad for similar specialty courts in Ellis County.

“There are several other specialty courts out there that I hope my position and us standing up with this program will really serve as the proof of concept needed to show the value behind these programs so we can help these communities,” Dorrough said.

He pointed to Tarrant County, which has several specialty court programs such as one that focuses on first responders and one that focuses on mental health.

But the first step is to reach out to help those who took an oath to protect the country.

“They’ll know this isn’t an easy program, some get-out-of-jail-free card,” Dorrough said. “It’s going to be harder on them, but we know they’re the kind of people who can buck up and do it. They were disciplined individuals at some point in their life, and we’re going to help them remember that to get them back on track.”